Has The Intended Purpose Of The Invention Of Photography Changed Since It Was Originally Invented

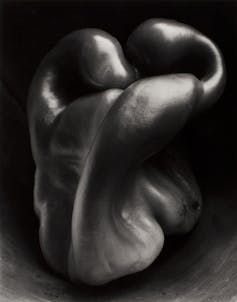

Much like a painting, a photograph has the power to move, engage and inspire viewers. It could be a blackness-and-white Ansel Adams landscape of a snow-capped mountain reflected in a lake, with a sharpness and tonal range that bring out the natural beauty of its subject. Or it could Edward Weston'due south close-up photograph of a bell pepper, an prototype possessing a sensuous abstraction that both surprises and intrigues. Or a Robert Doisneau photograph of a man and woman kissing near the Paris city hall in 1950, a picture has come up to symbolize romance, postwar Paris and spontaneous displays of amore.

No i would question that photographs such equally these are works of art. Art historians can explicate the technical and artistic decisions that elevate photographs by the masters, whether it's Weston's use of a tiny aperture, Adams' printing techniques or Doisneau's distinctive aesthetic. Information technology'south articulate that Pepper No. 30 belongs in a museum, even if a selfie posted on Facebook doesn't.

Oddly plenty, information technology was not always this way. Photography has not however celebrated its 200th birthday, yet in the medium'south first century of being, there was a great deal of debate over its artistic merit. For decades, even those who appreciated the qualities of a photograph were not entirely sure whether photography was – or could exist – an art.

Science or art?

In its offset incarnation, photography seemed to be more than of a scientific tool than a form of artistic expression. Many of the earliest photographers didn't fifty-fifty call themselves artists: they were scientists and engineers – chemists, astronomers, botanists and inventors. While the new form attracted individuals with a background in painting or drawing, even early on practitioners similar Louis Daguerre or Nadar could exist seen more as entrepreneurial inventors than as traditional artists.

Earlier Daguerre invented the daguerreotype (an early grade of photography on a silver-coated plate), he had invented the diorama, a form of entertainment that used scene painting and lighting to create moving theatrical illusions of monuments and landscapes. Before Nadar began to create photographic portraits of Parisian celebrities like Sarah Bernhardt, he'd worked as a caricaturist. (An aeronaut, he too built the largest gas balloon ever created, dubbed The Giant.)

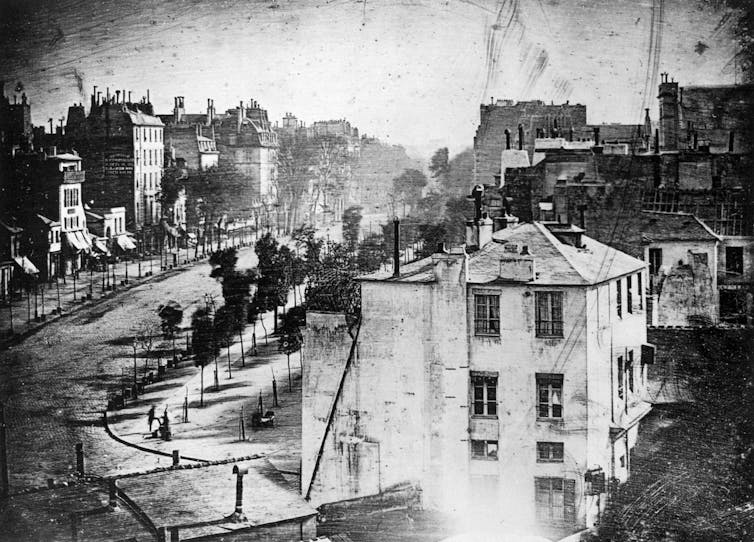

One reason early on photographs were not considered works of art because, quite only, they didn't look like art: no other class possessed the level of particular that they rendered. When the American inventor Samuel F B Morse saw the daguerreotype shortly subsequently its first public demonstration in Paris in 1839, he wrote, "The exquisite minuteness of the delineation cannot be conceived. No painting or engraving ever approached it."

A photograph of a haystack, with its thousands of stalks, looked visually staggering to a painter who contemplated drawing each one so precisely. The textures of shells and the roughness of a wall of brick or stone suddenly appeared vividly in photographs of the 1840s and 1850s.

For this reason, it's no surprise that some of the earliest applications of photography came in archaeology and phytology. The medium seemed well suited to certificate specimens that were complex and minutely detailed, similar plants, or archaeological finds that needed to be studied past faraway specialists, such as a tablet of hieroglyphics. In 1843, Anna Atkins produced Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions – considered the first volume illustrated with photographs.

Finally, the genesis of a painting, drawing or sculpture was a human hand, guided by a human eye and listen. Photographers, by contrast, had managed to fix an image on a metal, paper, or glass support, only the prototype itself was formed past calorie-free, and because information technology seemed to come from a car – not from a human being hand – viewers doubted its artistic merit. Even the discussion "photograph" means "light writing."

Critics counterbalance in

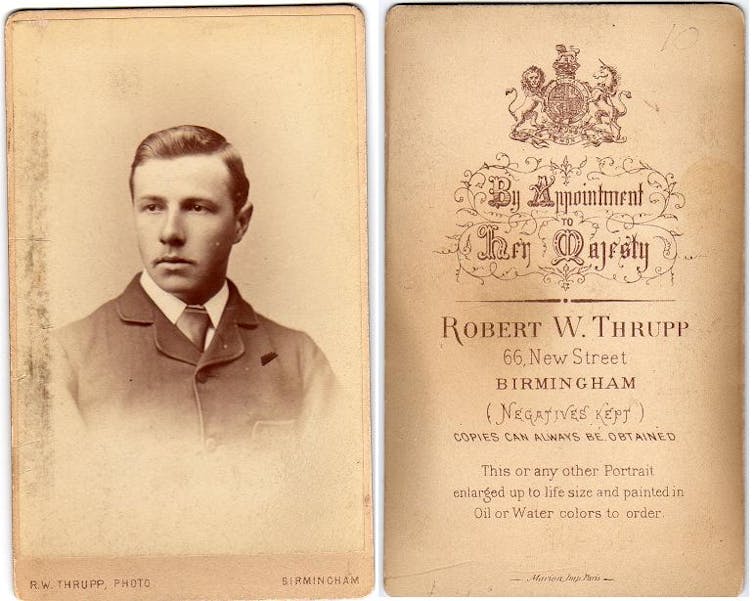

Before the photograph, painted portraits had well-nigh always flattered the client and conformed to the fashions of the mean solar day; meanwhile, the earliest photographic portraits didn't.

Elizabeth (Lady) Eastlake, one of the foremost 19th century writers on photography, listed many of the photograph's shortcomings when it came to rendering the female face. In a black and white photograph, blue eyes looked "every bit colourless as water," she wrote, blonde and red hair seemed "as if it had been dyed," and very shiny hair turned into "lines of light as big as ropes." Meanwhile, she noted that the male caput, with its rougher skin and bristles or moustache, might have less to fear, just still suffered a distinct loss of beauty in the photographic portrait. To Lady Eastlake, the photograph, "however valuable to relative or friend, has ceased to remind us of a piece of work of art at all."

Debate over photography'southward status as art reached its apogee with the Pictorialist movement at the cease of the 19th century. Pictorialist photographers manipulated the negative by hand; they used multiple negatives and masking to create a single impress (much like compositing in Photoshop today); they applied soft focus and new forms of toning to create blurry and painterly effects; and they rejected the mechanical look of the standard photograph. Essentially, they sought to push the boundaries of the grade to make photographs appear as "painting-similar" as possible – perhaps as a fashion to have them taken seriously equally art.

Pictorialist photographers found success in gallery exhibitions and high-stop publications. Past the early 20th century, however, a photographer like Alfred Stieglitz, who had started out as a Pictorialist, was pioneering the "straight" photo: the printing of a negative from border to edge with no cropping or manipulation. Stieglitz also experimented with purely abstruse photographs of clouds. Modernist and documentary photographers began to have the medium's inherent precision instead of trying to brand images that looked like paintings.

"Photography is the most transparent of the art mediums devised or discovered by human," wrote critic Clement Greenberg in 1946. "It is probably for this reason that it proves so difficult to make the photo transcend its well-nigh inevitable office as certificate and human action equally piece of work of art as well."

Nevertheless, well into the 20th century, many critics and artists continued to view photography as operating in a realm that was not quite fine fine art – a contend that even continues today. Just a expect dorsum to the 19th century reminds usa of the medium's initial shocking – and confounding – realism, even as photo portraits printed on calling cards ("carte du jour de visites") were becoming as fashionable and ubiquitous equally Facebook and Instagram today.

Source: https://theconversation.com/how-photography-evolved-from-science-to-art-37146

Posted by: cameronandso1947.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Has The Intended Purpose Of The Invention Of Photography Changed Since It Was Originally Invented"

Post a Comment